Keeping the Ocean

At Bay

How the Design for the New Treasure Island Reckons with Sea Level Rise

In 1936-37 man-made Treasure Island was fabricated at sea level in San Francisco Bay. It is now being redeveloped into a sustainable neighborhood of some 8,000 homes and a visitor destination.

This requires making the island resilient in the face of sea level rise, a serious anticipated consequence of climate change.

Even at birth Treasure Island seemed vulnerable to the waves. Mitigations for sea level rise are built into all aspects of its redevelopment. (Treasure Island Museum, 1937)

Captain Eugene Rideout of the Southern Pacific Railroad is often credited as the first, in 1920, with the idea to build an island atop Yerba Buena Shoals.

(Treasure Island Museum/ San Francisco News,1938, clip courtesy of Eugene Rideout)

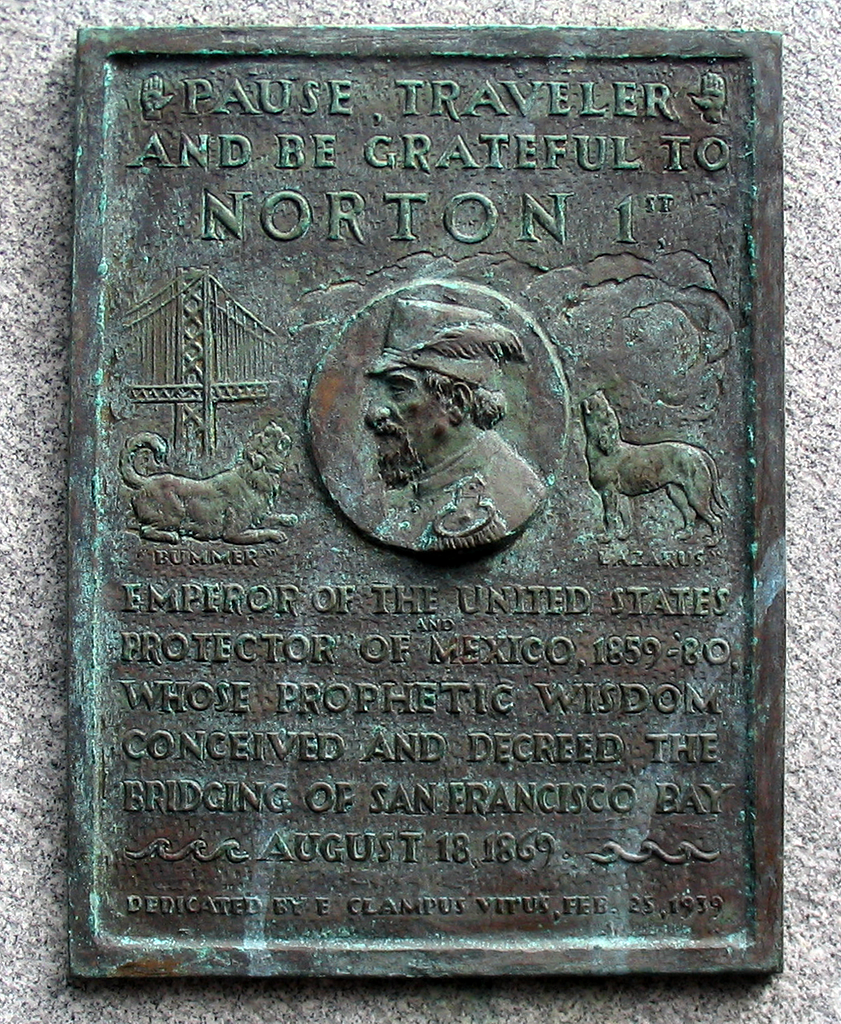

However, Rideout was not the first. San Francisco's self-styled Emperor Norton issued two prophetic decrees in 1869, one -- to use fill to make an island on top of the shoals and two -- to build a bridge from Oakland via Yerba Buena Island to San Francisco.

(Photo by H.W. Bradley or William Rulofson, via Wikimedia Commons)

This plaque on the old Bay Bridge recognized Norton's decree. It now decorates the overlook for the new Bay Bridge. (Wikimedia Commons, 1959)

The island's first event was the Golden Gate International Exhibition, a world’s fair, 1939-1940. After the fair closed, with World War II looming, the U.S. Navy transformed the island into a base, which remained active until the end of the 20th century. In the last 25 years, a diverse community has grown on the island of more than 2000 people, including families, living in repurposed naval housing.

On clear days in 1939-1940, the Golden Gate International Exhibition's Tower of the Sun was visible from the mainland. The Treasure Island redevelopment includes a tall mixed-used tower near the same site. (Treasure Island Museum, 1938)

Gothic-esque, the Tower of the Sun epitomized the remix of architectural styles that characterized the fair. The tallest structure, it was billed as "a beacon to Pacific unity." At night the entire fair was lit up in a spectrum of colors. (Treasure Island Museum/Paul Totah, 1939)

The field of flowers sat beside the fair's Elephant Towers. They were named for the decorations atop the building's pinnacles — pachyderms wearing howdah saddles. (Treasure Island Museum/ Paul Totah, 1939)

The elephant details were inspired by the Terrace of the Elephants at Angkor Wat, a large city of ancient temples in Cambodia. The structure also paid homage to Aztec and Mayan architecture of Mexico and the Northern Triangle. (Treasure Island Museum/ Paul Totah, 1939)

In 1941 the island became a U.S. Naval Station, anticipating conflict, and sailors began arriving in 1942 soon after Pearl Harbor.

Here sailors march in their dungaree uniforms and dixie cup hats after World War II had begun. (The U.S. Navy, 1946)

The first eighteen WAVES, the name for the women's naval reserve during WWII, also reported for duty on Treasure Island in 1942. As their number grew, they worked as instructors in the training schools, in the dispensary, the commissary, the hospital and across the island and its operations. (Women were not assigned to units tasked with direct combat in the U.S. Military until 2013.)

Over the course of the war the number of WAVES grew to 800 and filled six barracks. WAVES had a beauty parlor, their own mess hall and were assigned WAVES-only time slots in the recreational facilites, as well as their own sections for entertainment in the base's three theatres.

(The U.S. Navy, 1946)

In World War II, Naval Station Treasure Island processed 12,000 personnel per day for Pacific area assignments. The base was like a small city, serving all the needs of the sailors and naval administration.

Here are two WWII big bands on the island. The U.S. military remained segregated until 1948. The Navy, however, had banned discrimination two years prior.

(The U.S. Navy, 1946/Treasure Island Museum)

(Treasure Island Museum, courtesy of Steefenie Wicks)

Treasure Island’s 400 acres will be completely transformed in the next fifteen years by its redevelopment. Navy quarters for "married enlisted men" converted to affordable housing, will be razed. Redevelopment will bring 8,000 new homes, including 2,173 affordable housing units to Treasure Island and Yerba Buena Island. The first new condominiums will be completed in early 2022, and the first 100% affordable building – developed in partnership with Swords to Plowshares and intended to provide housing for veterans – will be completed later in the year. The first 1,300 new units are scheduled to be completed by the end of 2024. .

(Treasure Island Museum/Michael Hennahane)

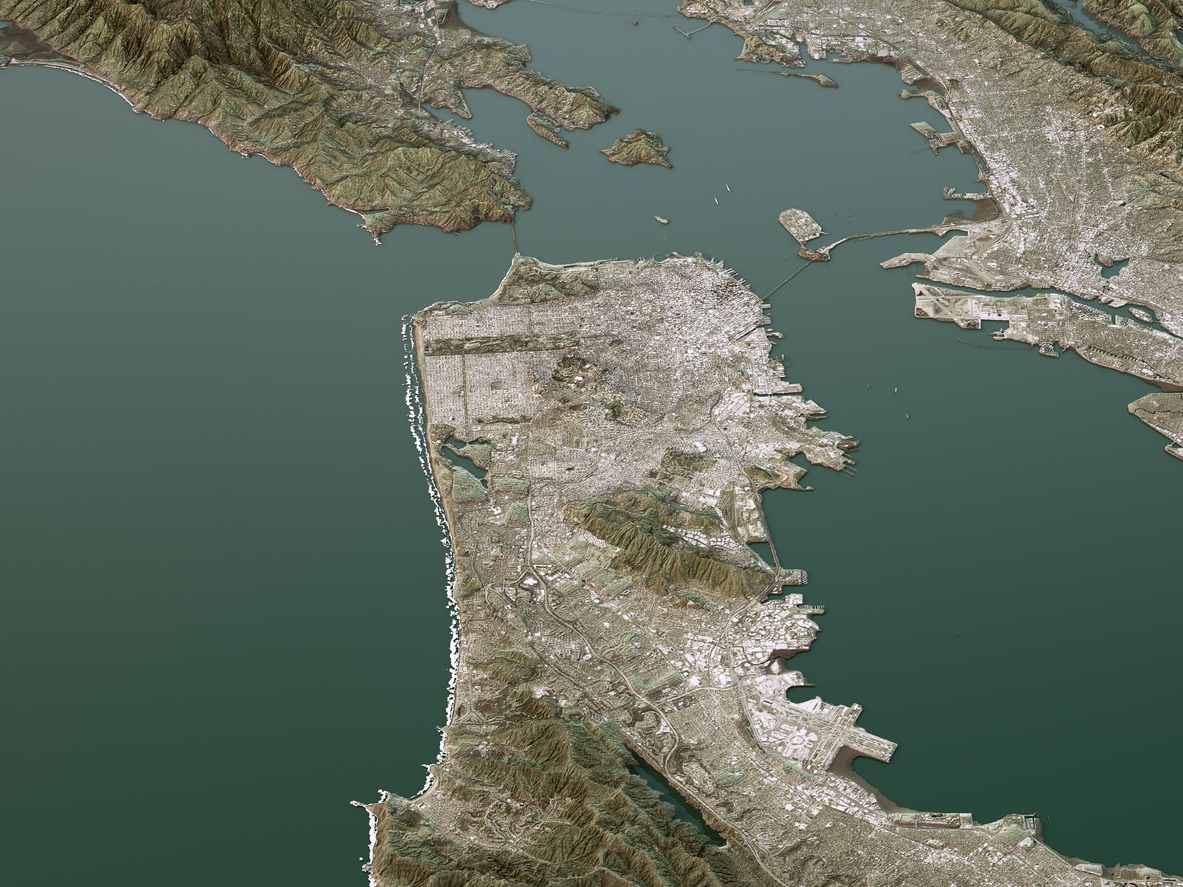

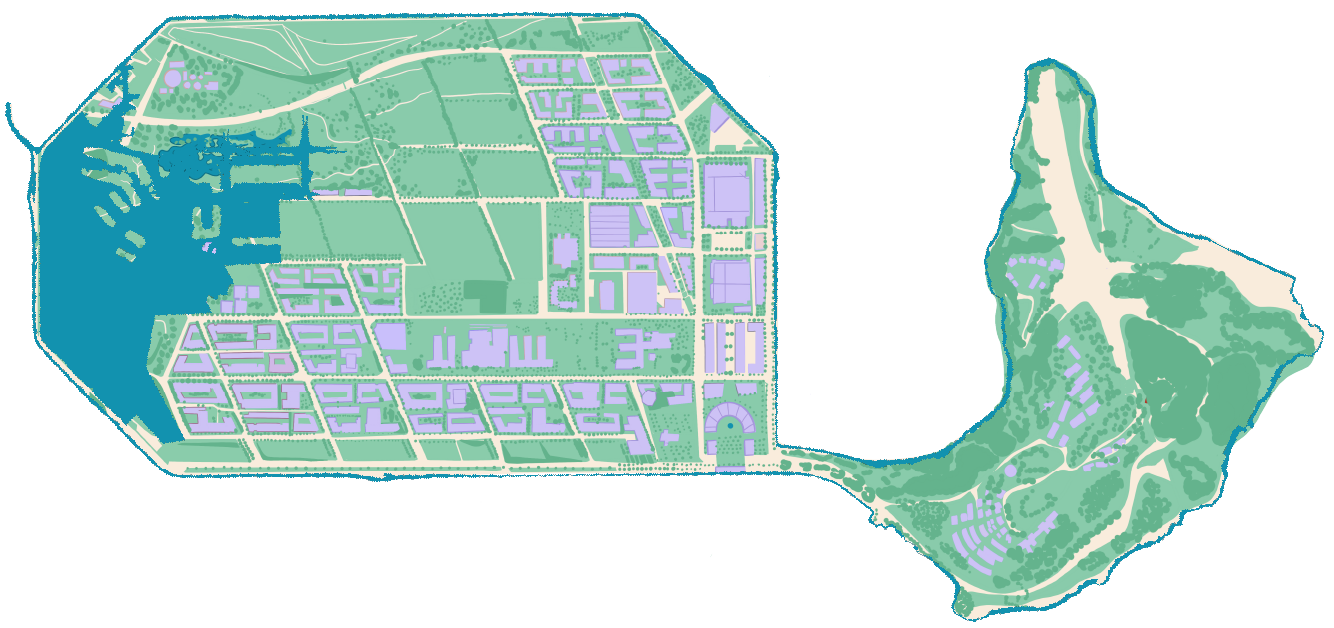

The comprehensive redesign addresses all identified environmental problems, including excess water from sea level rise (SLR). By 2035, the redevelopment of Treasure and Yerba Buena Islands is scheduled to be complete: a small, sparkling, San Francisco city annex, with parks, shops, services and 8000 new homes. The design philosophy for the new place, driven by the City and County of San Francisco, is based on sustainability and inclusivity.

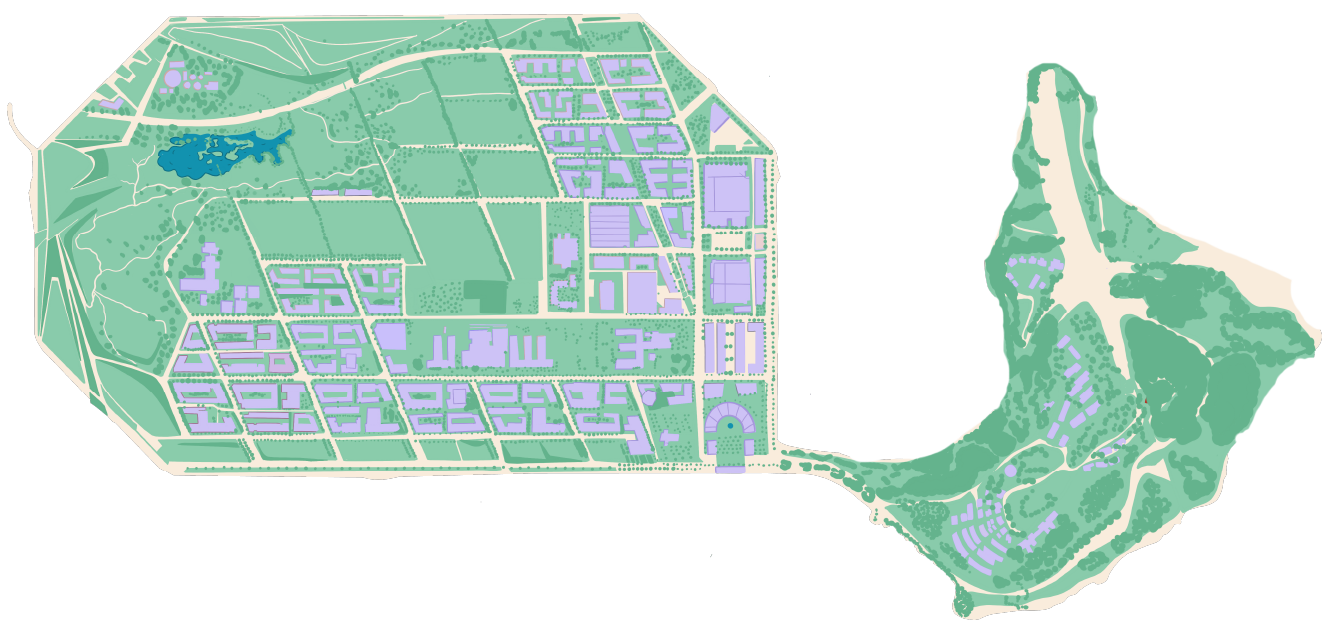

The new Treasure Island and neighbor Yerba Buena Island, also part of the redevelopment, will provide 290 acres of publicly accessible land, including 22 miles of walking, hiking and biking paths [The Treasure Island Development Authority, styled below as (TIDA) and Treasure Island Community Development (TICD), 2011]

Flooding has always been part of Treasure Island’s landscape, even before SLR began to accelerate. There is wave overtopping, meaning that during storm surges and at the highest tides, waves break over its vintage, human-crafted edges and cause small saltwater floods.

The 1930s-made Treasure Island also floods with rainwater. Ever since the Navy paved the island, it has been pockmarked with ponding stormwater that can make walking and driving difficult. The development plan responds to problems of both ponding and SLR, envisioning a new, more habitable place for as many as 24,000 residents, plus commercial and non-profit businesses and service organizations.

This San Francisco Planning Department map shows an upper range SLR projection and flooding at the end of the century on the mainland. The map models 66” inches of SLR, also the projected, upper range number in use by the Treasure Island Development Authority (TIDA) and partners in planning adaptive design features for the new development. (City of San Francisco Planning, 2021)

Waves from a king tide overtop San Francisco's Pier 14. Yerba Buena Island is in the distance. (https://twitter.com/burritojustice, 2021)

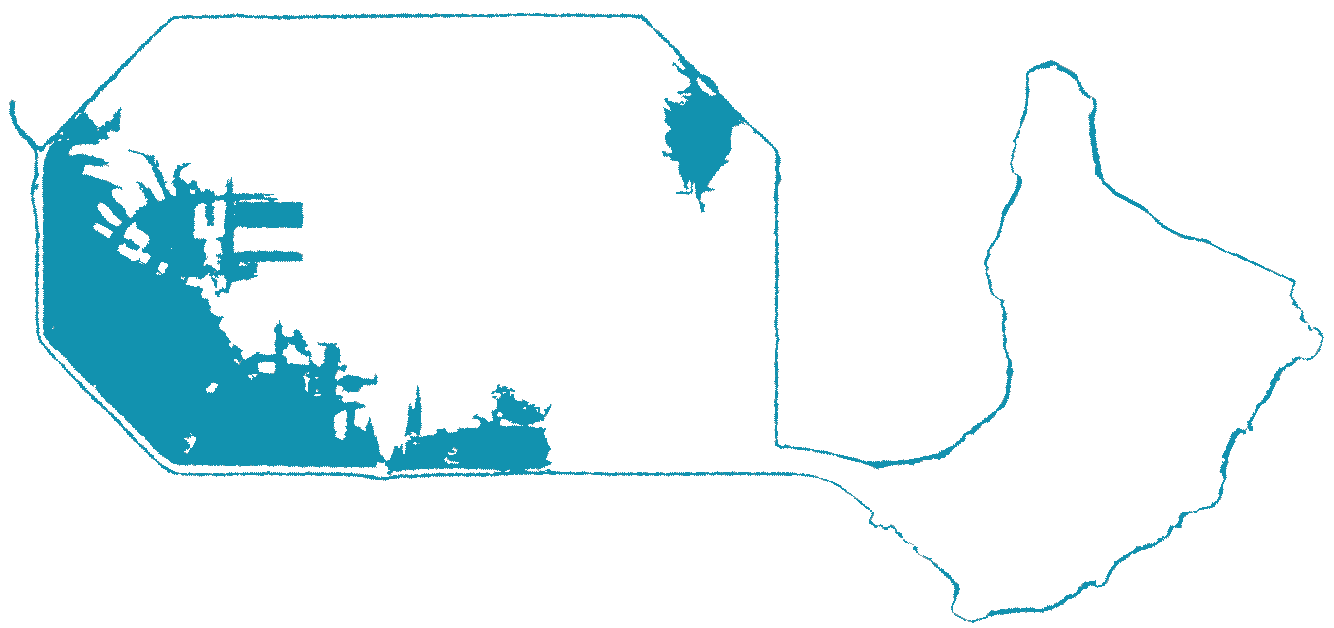

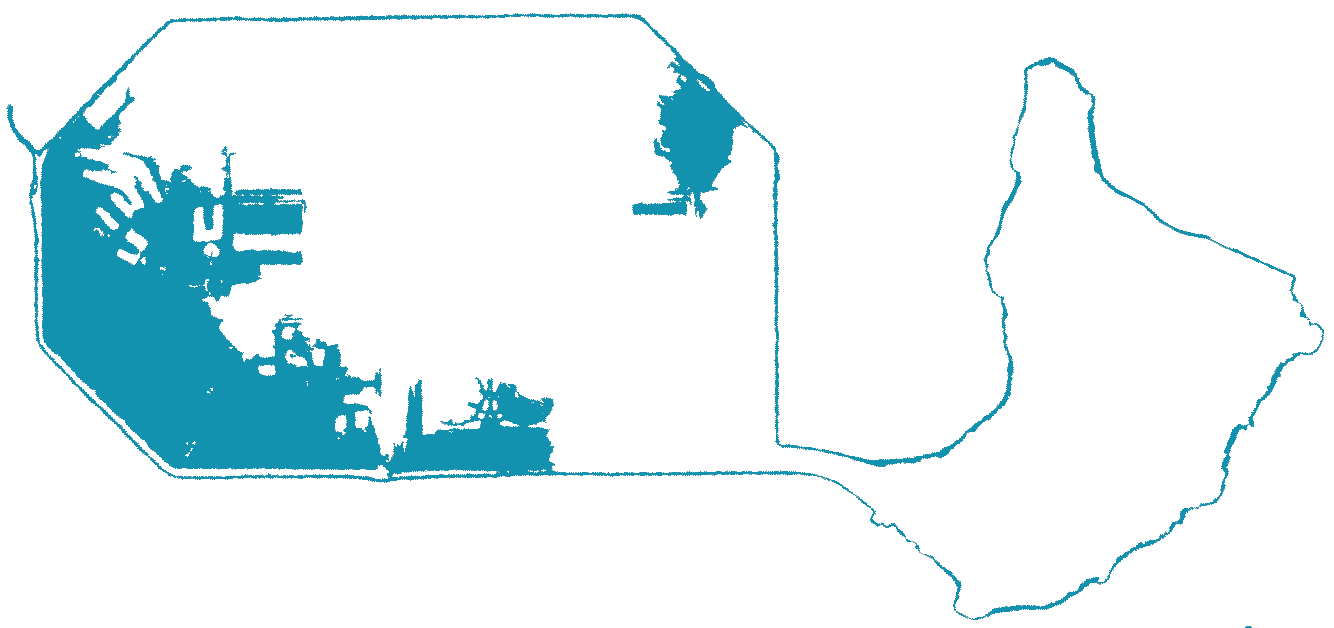

This is a rendering of the year 2100, projecting which parts of the Bay Area are most threatened by future SLR, combined with current rates of subsidence. Subsidence rates indicate how fast a particular piece of land is sinking. Without the reimagining of the island and its landscape, the northwest corner of Treasure Island would continue to sink at a fast rate. It has declined, however, and since 2004 the subsidence rate has deaccelerated by 40 per cent.

Nevertheless, without the interventions planned, the northwest corner of the island would subside faster than the threatened areas of the San Francisco mainland. The redevelopment will protect this most vulnerable part of Treasure Island by creating wild park land and wetlands to absorb excess water from both waves and rain. The parks and wetlands will also work as a natural recycler of the waters.

(Shutterstock, 2021)

Treasure Island &

Sea Level Rise

The developers broke ground on the redevelopment of Treasure Island in 2016, beginning with large geotechnical improvements. Included in this first work phase are cutting edge techniques to densify the soil and remove water in the mud-fill originally used to construct the island in the 1930s. The perimeter of the island is also being shored up. The new Treasure Island is expected to be complete, including all buildings, infrastructure, parks and open spaces, in 2035. Adaptation to sea-level rise (SLR) is an integral part of the plans, as the old island was extremely vulnerable to the rising Bay. Mitigations are planned to be adaptive. The goal is resiliency in the face of uncertainty regarding the extent of possible SLR

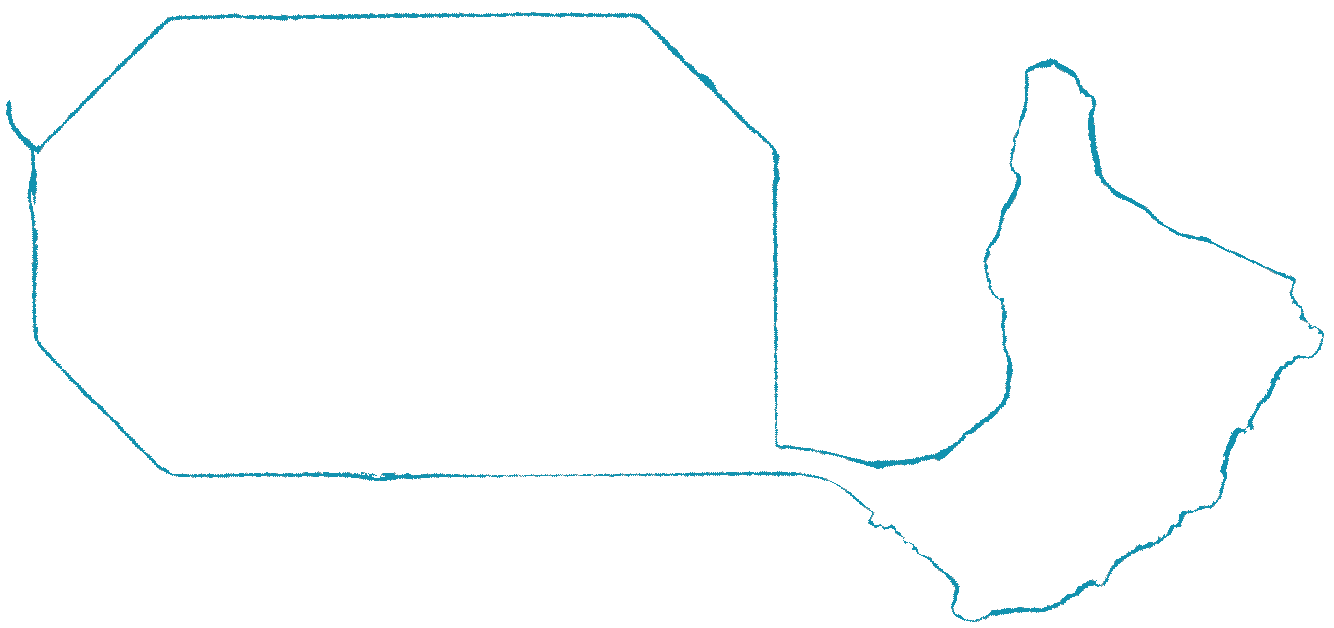

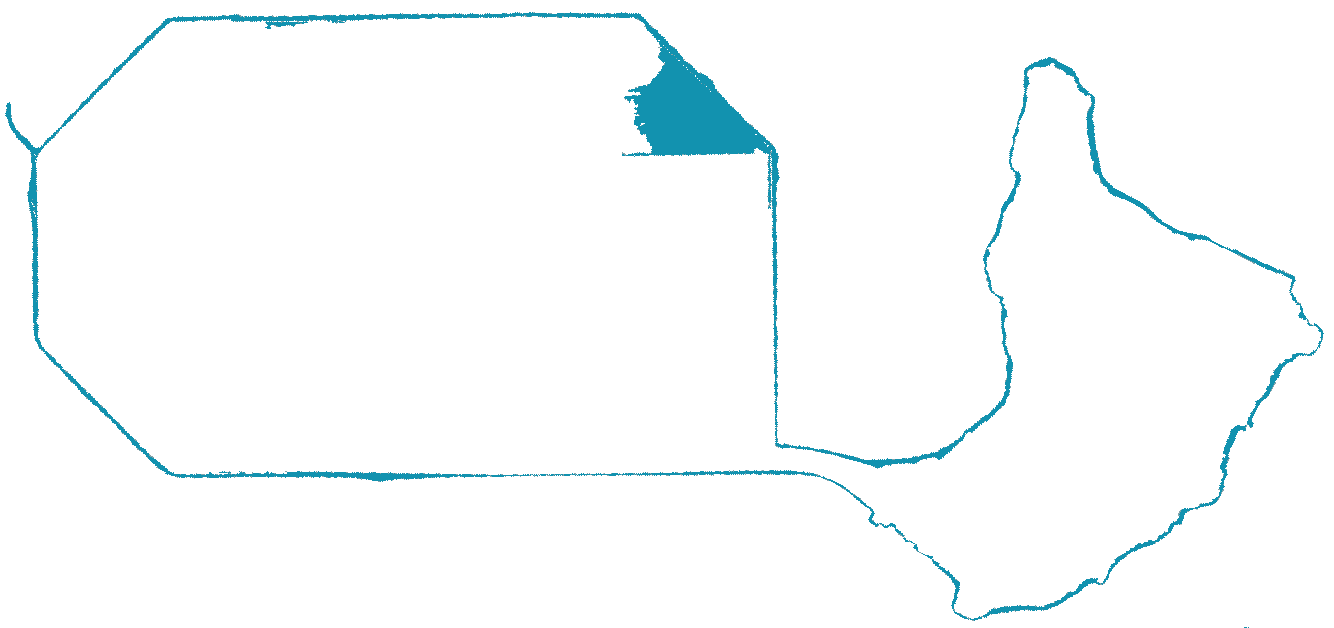

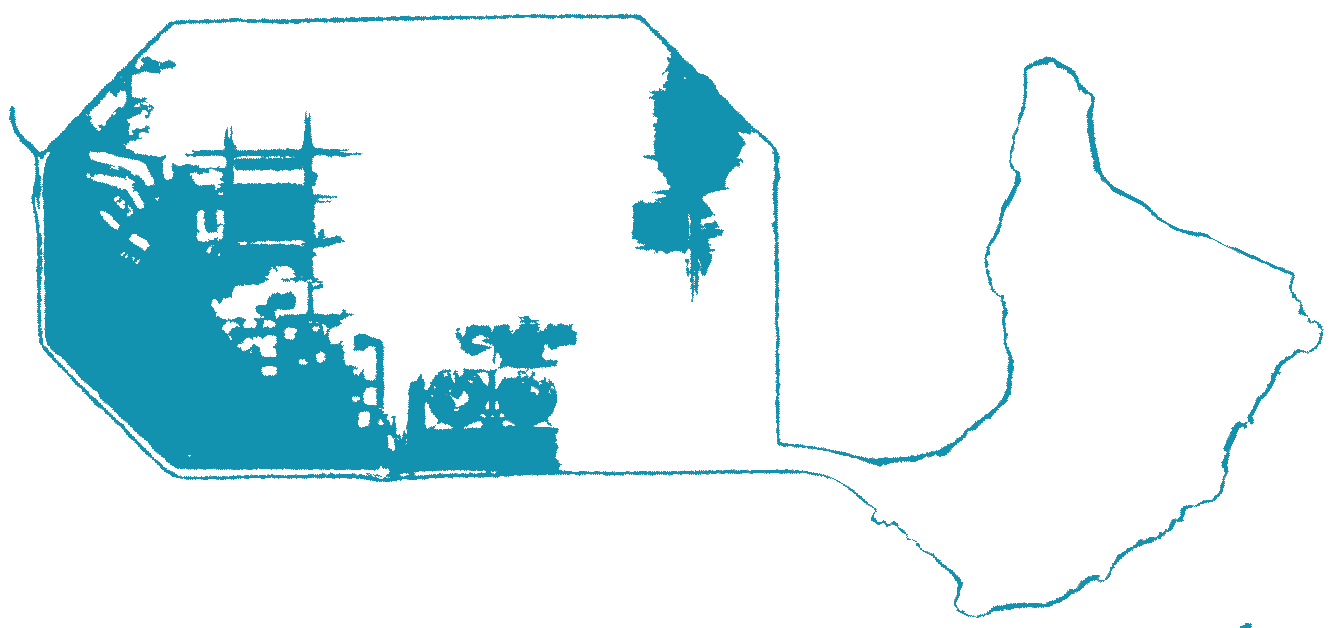

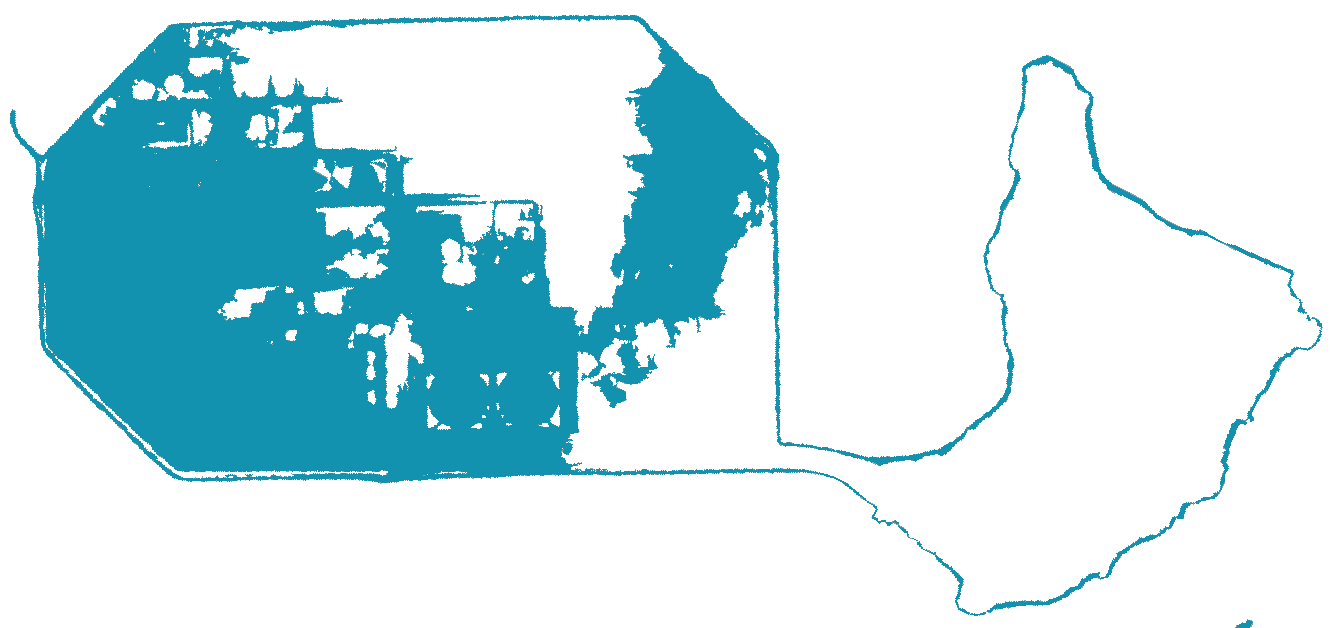

Toggle the buttons in the dynamic flood maps below to show probable flooding on Treasure Island if powerful storms were to occur in 2022, 2035, and/or 2050. The map on the left shows sea water inundation if the proposed adaptation measures are completed, while the map on the right shows what flooding would look like if the redevelopment were not to happen. The landscape at the north and northeast of the island will become open space and wetlands, an essential part of SLR mitigation as it can absorb flooding that in turn will nourish the island’s ecosystem.

With redevelopment

Without redevelopment

4 inches

7 inches

11 inches

2022

2035

2050

The first round of Treasure Island’s redevelopment is designed to protect the building and infrastructure against flooding between now and 2070 and open spaces until 2050. Nevertheless, it is possible there will be significant flooding in the event of a storm more powerful than those that cause 100-year floods.

Under such scenarios, new open space, wetlands and a 300 foot buffer between buildings and the island’s perimeter will mitigate the effect of waves that breach the shoreline. Elevated construction pads will keep flood waters out of buildings and other critical infrastructure. This image shows how wetland, green spaces and the elevated pads will protect buildings and people if such a flood occurs in the next 30 years.

The flood simulations in this Treasure Island & SLR tool show possible effects of a 100-year flood. The exact rate of sea level increase over the next 30 years is unknown. It will be determined by how quickly glaciers melt and oceans warm. We show two different possibilities here. The medium projection includes 11” of sea-level rise from 2000 to 2050, while the high anticipates 24” of SLR in the same period. In addition, the developers’ design strategies and construction plans are flexible enough to accommodate greater SLR -- up to 36“ --for the areas where residential and commercial real estate will be built. A minimum of 16” of SLR is the plan for The Wilds and other open space areas at the north of the island, where fresh and ocean water will be absorbed by the greenery. Greater levels of protection are planned should sea levels exceed the current projections.

A 100-year flood is a hypothetical scenario that scientists and engineers commonly use to assess flood risk. Based on past data, the metric represents a flood that should occur on an average of once every hundred years, when storms, tides, and tsunamis are taken into account. Exactly when such an event occurs is random, so such a flood may occur more than once in the next century if Treasure Island is unlucky. When a 100-year flood occurs, it will be destructive unless appropriate protection and adaptation measures are taken, such as those proposed in the redevelopment plan.

Shoreline communities, especially those situated on legacy low-lying land, such as Treasure Island before redevelopment, are extremely susceptible to damage from tides and storm surges because of SLR caused by climate change. The severity of storms is increasing along with the volume of the oceans.

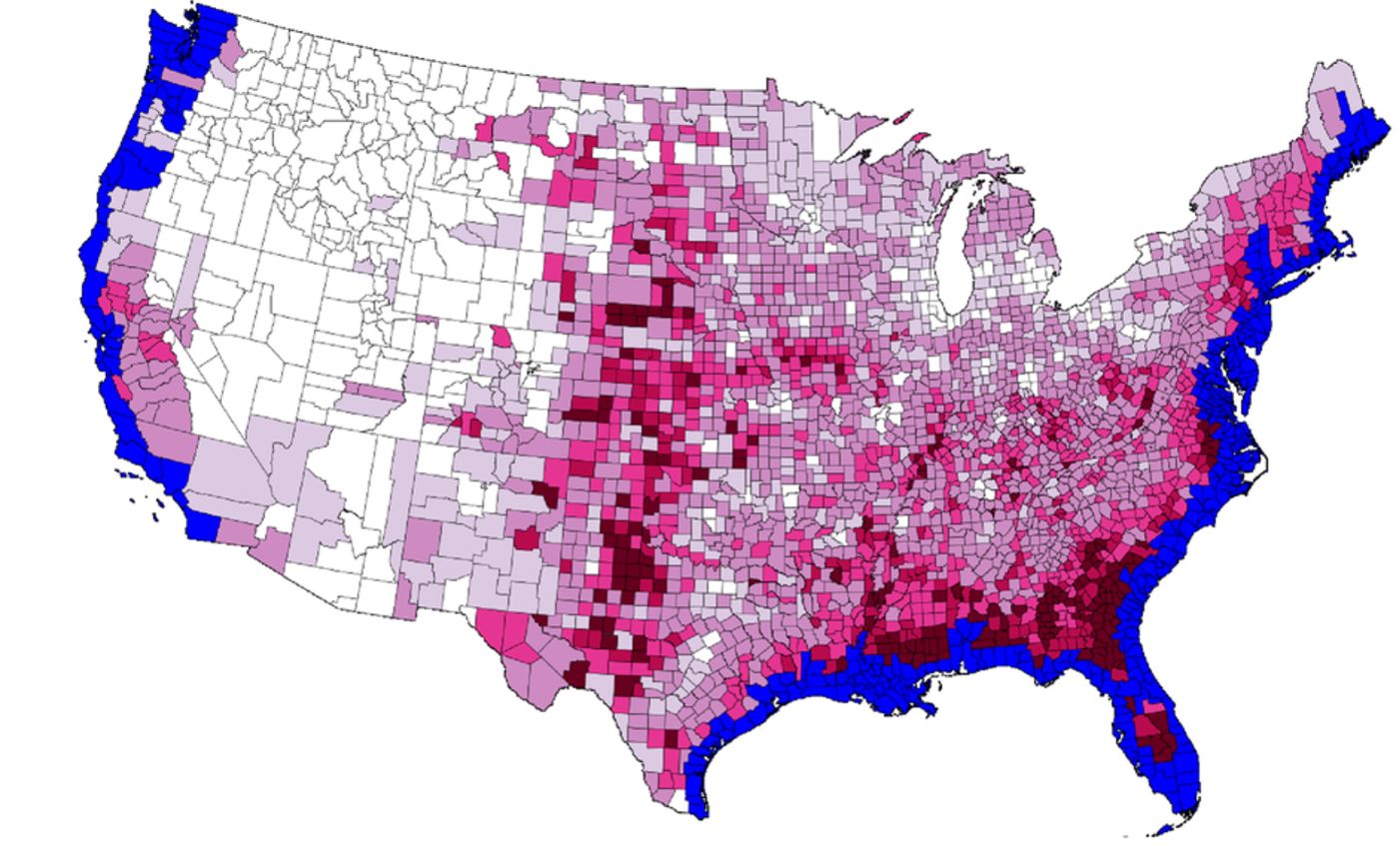

These conditions affect coastal areas all over the world. In the U.S. alone in the next 80 years -- within the lifespan of a baby born today -- a conservative estimate is that the lives of 13 million people will be altered by SLR. Many homes and properties will flood and people will be forced to move inland.

Treasure Island has mitigation plans in place, already in progress. Most coastal communities do not. Without adaptive design strategies similar to Treasure Island's, places along the shore will flood and residents will become climate refugees. Rapidly increasing populations will negatively impact local, inland governments, infrastructures and services if they are not prepared.

This map illustrates the probability that by 2100 as many as 13 million people in U.S. coastal communities will be forced out of their homes and businesses due to sea level rise. The red and light purple counties show where they are most Iikely to settle once displaced. (Bloomberg/plos.org © 2020 Robinson et al, Creative Commons Attribution License)

When Category 3, Hurricane Katrina roared into New Orleans on August 29 2005, close to 1800 people died along the Gulf coast, almost all of them low income.

Despite a mandatory evacuation order for greater New Orleans, at least a tenth of the city’s population remained, especially in the lowest lying and poorest areas of the city. Some stayed in their homes for emotional reasons, but many remained because they lacked communications technologies, financial resources or transportation.

This is what flooding looks like: in 2005 waters from Hurricane Katrina destroyed this New Orleans home. (The U.S. National Archives/ Jocelyn Augustino/ FEMA)

In many parts of the city, Hurricane Katrina's waters did not recede until weeks later. The waters' retreat revealed more, different scenes of catastrophe. (picryl/The U.S. National Archives/Andrea Booher/FEMA, 2005)

Rescue efforts the day after Katrina (picryl/The U.S. National Archives/ Jocelyn Augustino/FEMA, 2005)

On Treasure Island the entire current population is low to middle income. The residents number slightly more than 2000, similar to the number of lives lost in Katrina. However, before that storm there was never a redevelopment plan for the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, nor for New Orleans, nor, for example, for its Lower 9th Ward, one of the poor parts of the city that was particularly hard hit by the catastrophic flooding.

The plan for Treasure Island is already in progress. It’s an SLR-conscious redesign and geotechnical reengineering of all 400 acres, with an inclusionary housing plan for current residents. A new multimodal transportation hub will be one of the first things to be completed.

About 50 percent of current Treasure Island residents are low income. The non-profit One Treasure Island (OneTI) serves as an umbrella for social sevices, including food banks, such as the one pictured here. (One Treasure Island)

One TI's Construction Training Program equips residents with skills to find work on island and off with developers. Those trained include formerly homeless and formerly incarcerated individuals. (One Treasure Island, 2020)

Proposed housing model for the new development (Treasure Island Community Development, 2020)

Without this island redo over the next fifteen years, if a major storm were to hit Treasure Island, there’s little doubt that many members of the current community would suffer as did those in Louisiana during Katrina. By 2035, the population is expected to grow to 24,000 residents. This entire, much larger community will be protected from rain and sea water flooding by the improvements described in this exhibit.

A small fraction of the New Orleans homes lost to flooding from Hurricane Katrina (picyrl/Jocelyn Augustino/FEMA 2005)